Inspired by an article from Mark McKergow

The character, qualities and competencies of leadership are under scrutiny. In politics, the business world, sports and the Christian sphere, it’s possible there has never been greater interest in and controversy over what healthy leadership entails. None of us can escape the topic. Perhaps you consider yourself a leader, and perhaps you do not. Either way, we all encounter leaders and leadership.

This article does not attempt to answer the entirety of the question as to what healthy leadership looks like. Instead, I invite you to join me in reflecting on the concept of “leader as host, host as leader” inspired by a paper I read last year. Let’s begin with the image of Jesus as ‘host’.

On the night of his betrayal Jesus hosted his disciples. He arranged the venue (Luke 22:10), and asked his followers to finish preparations (Luke 22:13). He fulfilled several different leadership functions by taking initiative, directing and delegating. Perhaps the most intriguing part of that evening, at least from a leadership perspective, was the way he functioned as host. What lessons might there be for us regarding hosting and healthy leadership?

Leader as hero

“The idea of a leader as a heroic figure is deeply ingrained in our society.” Indeed, there are times when a warrior-type heroic leader is needed. However, I doubt there are many today who view this model of leadership to be the healthiest in the long term.

“…with the postmodern world of ever-greater connectedness, multiple perspective and ‘swamp issues’ – issues which are messy, interconnected, not amenable to quickfire technical analysis – the commanding-and-controlling hero has never looked more out of place.”

McKergow

Our churches in the UK and Ireland are complex environments. The fact they have been around for several decades makes them inevitably so. A glance at the Epistles reveals the early church had its ‘swampy’ issues. The approach of Paul and the other writers was not that of the hero leader. Perhaps they understood the many shortcomings of that model. These include:

- “The hero leader is seen as all-knowing and the followers all-dependent; the people cannot rescue themselves but rely on the appearance of the hero.

- “The illusion of control – by being all-knowing and strong and brave, the leader can avert disaster by their own efforts alone. The interdependent and complex world is not so amenable to this outlook.

- The homogeneous imagery of the followers – kings have subjects, shepherds have flocks of sheep. This seems to suggest homogeneity amongst the masses. All the followers are the same and therefore can be thought of as one (rather than individuals).”

Any leader worth their salt accepts they are not all-knowing, they cannot control everything, and that not all they lead are the same. However, the allure of a simpler way to lead is strong.

Given these weaknesses, what is the alternative?

Leader as servant

The servant leader model has become popular in both secular and spiritual spheres in recent times.

“It brings to the fore the leader’s need to respond to their followers and sustain the community, to steward it and hold it in trust for future generations.”

McKergow

There are, however, challenges with utilising the servant leader model. For example,

- “The richness of the metaphor is not obvious.” The servant role in ancient literature was not the same as many people think of it today. It was not necessarily one of subservience, nor the inability to challenge the “master”. Even the slavery image (doulos) of the New Testament needs to be carefully interpreted. Slavery in first century Palestine is not exactly the same context as that of the African slave trade or modern slavery.

- “The image of servant is not a compelling one to those (for example women and ethnic minorities) who are traditionally cast in such a role.” Servanthood for such people has often been warped by expectations placed upon them which are not congruent with the example of Jesus and the teaching of the New Testament. Telling somebody who has been forced into subservience that they need to be a servant is going to be difficult to accept, and certainly not inspiring.

- “The leader as servant has similar hierarchical issues to the hero, but from the other end.” Is the servant at the whim of those he or she is serving? What accountability exists for the servant to accede to or, alternatively, countermand the expectations of those being served?

Considering the strengths and weaknesses of both the hero and servant model has helped me to more clearly articulate what I find problematic with both. The hero model was more obviously troublesome. The servant model seemed more immediately scriptural. However, something about it has never quite sat right with me – at least as a black-or-white alternative to the hero model. I cannot deny that Jesus taught servant leadership. I am aware that part of what troubles me might simply be that I don’t like leading that way!

We can affirm the value of the hero model in certain circumstances. We can affirm the servant model as being normative for leadership after the example of Jesus. But, is there a further leadership model which might enrich the way in which we lead and our expectations of those who lead us?

Leader as Host, Host as Leader

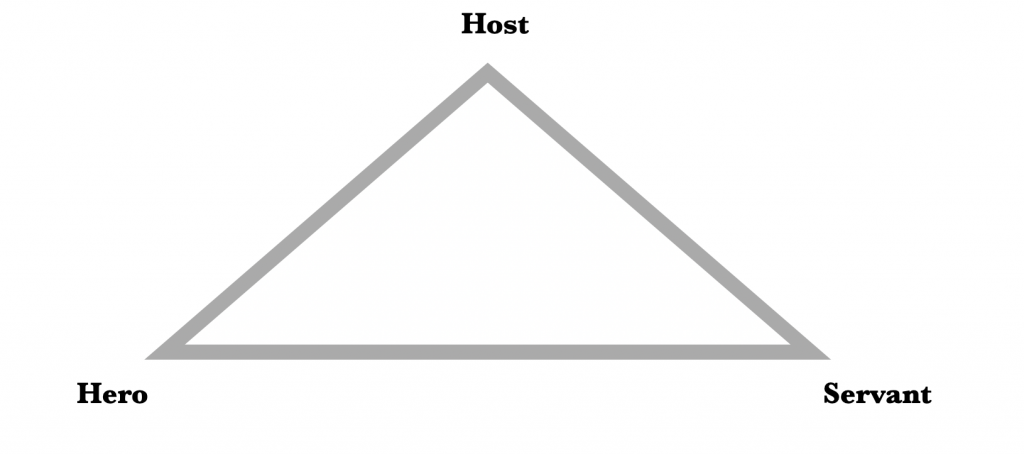

“We can look at hero and servant as opposing ends of a spectrum of hierarchical leadership”

Hero <———————————————————————————————> Servant

“It seems to me that the Host lies above the spectrum and it is a flexible and context-dependent role which sometimes necessitates hero behaviour, sometimes servant, and many inbetween possibilities.”

McKergow

- The host takes initiative by planning and inviting – a ‘hero’ characteristic. God acts in this way: “You prepare a table before me” (Psalm 23:5 NIV11; see also Matthew 22:1ff).

- The host serves the guests by ensuring they have a good time – a ‘servant’ characteristic. The host listens, responds and does not hog the limelight. Jesus came to give us life in all its fullness (John 10:10). His actions at the last supper in John 13 are a heady mixture of hero, servant and host.

Advantages of the host metaphor

- “It’s an everyday image”. We can all understand it, yet it is rich.

- “Hosting is an activity, rather than a defining characteristic of a person”. In some contexts we are a guest and in others we are a host. Jesus was both guest and host in Luke 7:36-50. A guest to the Pharisee, but host to the woman who anointed his feet with perfume. The possibility of swapping roles places all of us in a more interactive context and level relationship.

- “Hosting gives a definite feel of some responsibility for the success of the event. The Host has some authority – but they give it to themselves and earn/maintain it by doing the role well.” The responsibility is real, but it is only meaningful in as much as it brings success to the guests. The host may feel gratified by the success of the event as he or she perceives it to be, but the ultimate test is whether the guests depart glad they came.

Four elements of host leadership

- “Defining the event AND Responding to what happens.”

- “Engage and provide AND Join in along with everyone else.”

- “Protect boundaries AND Encourage new connections.” Keep out the gatecrashes, but help people make new connections and break down barriers.

- “Be the first AND Be the last.”

Reflections

What might leader as host and host as leader look like in a church leadership context? Many issues could be considered, but four follow. Let’s play with the image a little:

- Preaching and teaching

- The hero preacher is an annoyance, the subservient preacher is an object of pity. Can we do better? Is there a place for the host model? I refer not to the appropriately humble speaker, but those who appear to be ashamed of speaking in front of others.

- When we preach and teach are we operating as host, or guest? Leading a congregation in exploring God’s Word feels more like host than guest. As such, we are the one providing the food, but, crucially, not forcing people to eat it. If they don’t like what is served up our assumption cannot be that the fault is with them. What have we provided? Was it what they needed? Have we made it reasonably palatable? Have we forced people to stay longer at the table than they wanted? Have we made allowances for the ‘weather’?

- If God is our ultimate host, perhaps speaking to the congregation is more like being asked to offer a toast to the host. With this understanding, it may cause us to speak more about God, and less about us, our plans, our agendas, our hopes, our fears and what we expect of the congregation. Might God be seen more clearly if we were toasting him and thereby honouring him as host?

- Leading meetings of leaders

- Our role may change. At times we will find ourselves operating as a guest at meetings we are hosting. When someone speaks on a topic about which they know more than ourselves they become the host. Our insecurities are challenged. Are we willing to give up the host position, even if temporarily?

- Agendas will be flexible. Our guests arrive with experiences and matters on their minds about which we know very little (here and below, ‘guests’ does not refer to non-Christian visitors, but members of our leadership teams or congregations). If we proceed to tell everybody what to eat, what to drink, what to talk about, what games to play, where to sit and who to talk to, we will diminish the enjoyment of our guests at best, and bore or annoy them at worst. Furthermore, we will have prevented them from being enriched. An agenda is not the problem. The lack of flexibility is. The meeting should serve the attendees, not the organisation. Therefore, the following point ensues.

- Guests will influence the host. If I am leader and host, my primary consideration is the needs of my guests. What we talk about will be influenced by the group. The host will ask them what they need, request topics to be addressed, change the emphasis of teaching and discussion according to what they share, and be sensitive to their allergies and intolerances. If some in the group have had difficult discipling experiences, or some women have had challenging interactions with men in the past, or if others have previously been marginalised because of their race, it will do no good to either ignore those matters, or explicitly tell people to “give those things to God because we need to talk about the kingdom right now”.

Good communication prior to the event and flexibility during the meeting is more important than a neat agenda. Good hosts are skilled at responding in the moment to the interactions of their guests.

3. Planning and running church services

- Content. A good host does their best to provide what they believe their guests will find helpful and enjoyable. This applies in all contexts of being a host, not just in one’s home. For example, hosting a workshop. Have you ever been to one of those workshops which, over the course of two hours, teach you everything you already knew? How frustrating! The host of the workshop did not do their homework (hostwork?). Could we survey our members to discover whether what we are doing in our services and the balance of the different elements is working for them? No, we cannot please everybody all the time, but we can find out what would encourage them and make appropriate adjustments. Are our services too long, or too short? What about the content of the lessons? How about the priority of prayer? Are we reading enough scripture? Is there adequate time for fellowship? Are the children enjoying church? Do non-believers feel welcome? What about the way we do musical worship?

- Involvement. A host is successful inasmuch as they help all guests to feel valued and involved. A dinner party where five guests have all the fun while the other 25 watch on, bored and, possibly, resentful is not a successful event. This speaks to the way in which we plan church events. Are the same people prominent all the time? Are a small number of people involved in any given event? Is the group too large for most people to ever get involved? One of the blessings of our small Watford group (34 members) is that everyone is involved. In one way or another everybody does something ( In our most recent service nine different people (including children) were involved in reading, singing, welcoming etc.). Over the period of a month nobody, from eloquent to tongue-tied, is missed out ( Not that we are perfect. This week I received a call from a husband who noticed his wife had been missed out recently. I’m grateful he called me. It illustrates that our culture is healthy because it was his assumption that she would be involved. I will make sure she’s doing something this coming Sunday!). When people alternate between the experience of being a host and a guest during an event, their investment in said event is much more profound.

- Training the next generation of leaders

The younger generation are not interested in standing by and applauding their leaders. They want to know how much we care, whether we have what they need, and the authenticity of our faith.

- Listening. Good hosts are good listeners. Our training must respond to their particular and personal needs, not our predetermined agenda. It is said we tend to train people in the way that we like to be trained. Understandable, but misguided. If I have been given the privilege of hosting someone’s training, then it behoves me to put in the listening hours to discover their strengths, weaknesses, fears and hopes. Then and only then to co-create a training program with them. As an example, my personal experience of training the younger generation of leaders is that they prefer to receive feedback after the event rather than input beforehand. This is counterintuitive to me, and alien to my own training. But that’s the way it is! As one hosting their training, such a perspective challenges my assumptions.

- Letting go. Wise hosts curate events so that their guests will flourish. Hosts are not in control, though they are careful to protect their guests. If we are hosting young leaders’ training, we must give up the illusion of control. Instead, we honour them and the spirit of Christ in them, by providing them with opportunities to flourish. On occasion this will bring them and those they host great joy. On another they may fail. We are not in their lives to prevent failure. We are in their lives to support them as they learn. In light of letting go, the next point follows.

- Risking trust. The host risks much when they invite people into their home. Broken crockery, judgement passed on their choice of decor, the behaviour of their children and much more. Considering their weaknesses, Jesus demonstrated remarkable trust in his disciples. Do we really need to host every Bible study with a seeker? Do we even need to be involved? Part of training the next generation involves giving them space so that they themselves will learn how to be a host. How do those we are training feel? Do they sense we trust them? Do they believe we applaud their initiative – especially when it does not fit with our preferences?

Final reflections

The approach to and philosophy around Christian leadership is more polarised than ever in our culture – both in society at large and in our Christian circles. Some subscribe more to the hero model (whether consciously or subconsciously). Others to what I would see as a stylised servant model. Might there be an alternative? One which could bring the strengths of both together?

Perhaps leaders could see themselves as hosts, and hosts see themselves as leaders. It looks like Jesus did both. We are his followers. Let us imitate.

God bless, your brother,

Malcolm

- Inspired by article published as McKergow, M., W., (2009). Leader as host, host as leader: towards a new yet ancient metaphor. International journal for leadership in public services volume 5 number 1 pp 19-24. I read the paper as part of my training as an accredited Solutions Focussed coach.

- Material from McKergow’s article are in quotes